Sunday, October 22, 2006

Bride Kidnapping Again

Yesterday, seated with a group of local colleagues, I read an article about bride kidnapping in the local English-language newspaper. Human Rights Watch recently released a report condemning Kyrgyzstan’s inaction on bride kidnapping and domestic violence.

The article related the story of a 17-year-old, Feruza, who was kidnapped by a stranger on the night she was supposed to wed someone else.

“He forced me to have sex with him the first night,” she is quoted in the article. “A woman came to say that they’d prepared my bed; I thought I’d be alone. I lay down to sleep, then he came in and he forced himself on me and raped me. I was saying no and he still did it. I cried and screamed…There were other times, too, when he raped me. I didn’t ever want to go to sleep.”

I commented to two of my co-workers on the article. “How awful,” I said, “someone was kidnapped on her wedding night.” I couldn’t imagine all of the preparations and thoughts of a voluntary life together suddenly replaced by a life with a stranger, a stranger willing to use force and violence.

“That happens all the time,” Aizhana, a 33-year-old single mother said with a smile. “When a guy realizes he’s about to lose her to someone else, he reacts quickly.”

Nasikat, an unmarried woman in her twenties also laughed.

“That probably happened in the south,” Aizhana said.

“It happens here too,” Nasikat said. “In the villages around Bishkek. I have a friend who was stolen and taken back two times.”

They both giggled as I remained silent, but shocked at their light treatment of the matter.

A little later, while walking down the street with Aizhana, I told her that the article continued to bother me. One of the first cases of forced kidnapping I came across in Osh, a case I’ve written about in this blog, took place when the man made arrangements with a taxi driver to help him kidnap her. Being taken hostage in a taxi or car seems to occur relatively frequently.

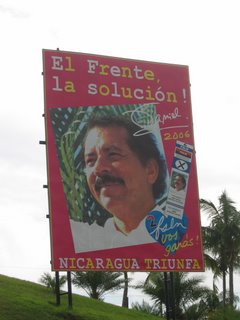

“After my experience in Nicaragua,” I told Aizhana, “I know what it feels like to suddenly be a prisoner in a car. It’s a shocking and traumatic experience. And for me, it was just one day. But for them, it’s the rest of their lives.”

“I know,” said Aizhana, with uncharacteristic gravity. “I think it’s because it happens all the time here that we just get used to it and treat it so lightly.”

At the same time, when I tell staff about what happened in Nicaragua, they look at me in disbelief.

“Is it such a dangerous place?” one woman in her early 20s asked me. “That would never happen here.”

And she’s right. I’ve heard of some cases of taxi drivers being victims – killed for their cars. But I’ve never heard of a driver himself being involved in harming his passengers.

I’ve been more cautious when taking taxis here, less willing to argue over price as long as I get to my destination safely. When I take a marshrutka, the public mini-buses, I’m amazed that I don’t need to worry about knife-bearing teenagers who could stick me up in public, while the rest of the bus would sit passively. That happens in Nicaragua, but not here.

Of course, this is a sign the society somehow functions better here – perhaps the closeness of the family is responsible. At the same time, violence against women is not uncommon. And women under the age of 25 are at constant risk of kidnapping, rape, and an entire life with someone they may not love.

Just because I’m not in the risk group, I feel safe here. But I wonder, does the localization of violence within the family unit, does the targeting of a rather helpless group (women aged 15-25), thus reduce the incidence of randomized violence? Do the young women in Kyrgyzstan bear the brunt for the rest of us? Is that why so many of them would like to get out?

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

I Love Kyrgyzstan

Today I arrived back in Bishkek, my beautiful, happy home. I felt at peace even while driving through Kazakhstan from the Almaty airport. We had to stop for cows on the major Almaty-Bishkek road, I saw the wide, gray sky, the empty, rolling, golden hills, the blue and white gingerbread box houses. I felt the calm of the land, the ability to be alone and be safe, to trust people more, to venture out and explore without fear of one’s neighbors.

I loved the romantic graves with moons on the corners of the fences, and how my driver, Sergei, a Russian, crosses himself when passing them. I loved the holy snow-peaked mountains – stark, clean, fresh and cool.

I feel like here, people are able to sense themselves as significant under the vast sky. They are part of the world, rather than locked behind bars where they can burn in flames or sweating out their troubles in the humid, stifling air.

Again, I’m silent. After six weeks without a word of Russian, the language has moved down in my head. I was too tired to struggle, so I spent most of the three-hour car ride in silence. It can be strange and frustrating to lose my voice, but it’s also a nice opportunity to be a silent observer. In a short trip out to buy basic supplies, I realized I still had the basics. And I still understand. It will probably just take me a few days to readapt.

It’s very cold here compared to Kyrgyzstan, a chill, fall windy air that portends sniffly noses and tightly pulled jackets, dreams of afternoons with a cup of hot tea and a book by the heater. It’s that time of year when it’s already cold but the central heat hasn’t yet been turned on.

So after several hours of jetlagged sleep, I spent the rest of my waking day in front of my portable heater, with a cup of hot tea, a book and a laptop. It’s great to be home.

Indo-Maiz Reserve

October 4, 2006

One good thing about an 8:30 bedtime is that it makes it easier to get up at 5:30. We met our tour guide at the docks at 6 a.m. and set off for the Indo-Maiz Reserve, a 43,000 hectare swath of tropical humid forest, spread out from 8 kilometers east of El Castillo all the way to the Caribbean.

We motored slowly through the rapids and downriver, the forest growing ever more dense as we traveled. We moved slowly over the glass-smooth water, the mist sometimes so thick we could barely see ahead. Egret, heron and the black anhinga flapped their wings upon our approach. The jungle – thick, dark, impenetrable – stood shrouded in the misty smoke.

Our tour included the rental of knee-high mud boots, which we needed for the muddy trail. We got off at a small dock on the edge of the reserve and waked up to the park ranger’s house to sign in. A many walked out, next to a large, tabby cat.

The cat walked with strong steps and looked at us with a menacing gaze. As soon as I commented on the strange cat, it began to hiss and head toward us. Turns out it was a baby ocelet. It approached each of us individually, hissing, and reached its paws around Mark’s leg. The ranger had a domestic cat as well, who didn’t seem too please with its new wild feline neighbor.

We entered the darkness and magic of secondary forest within minutes, following a muddy, but well-maintained two kilometer trail through the forest. An opaque stream ran through a green fantasy world of trees, flowers, vines, ferns birds, insects and animals. The sounds of the jungle inhabitants rang out around us, the coo of the paloma, the ribbet of the poisonous blue jeans dart frog, the fingernails over a washboard sound of the cigarra, whose singing increased in strength as the sun rose.

Walking through this world, I felt as though I were gliding through a secret world. It seemed the environment was ready to pull us down, eat us, make us succumb to natural forces and become a part of it.

We spotted the blue jean dart frog, a bright red miniature frog with a dark blue behind It’s so poisonous that just by touching it, the poison can seep in through a cut or wound. The native peoples used these frogs to poison their spears. We came across a small, poisonous vibora snakes, lodged in the corner of a step. Best of all, we saw lots of white-faced monkeys (called cappuccino monkeys), with white furry faces and brown behinds. They looked at us menacingly from the tree boughs and approached us in an attempt to intimidate us. But they never left their high perches.

We also saw some of the bounteous plant life lodged in the jungle – the 300 year old mountain almendro, that both feeds the great green macaw with its fruit and produces an oil that the bird uses to comb its wings. The ceiba, worshipped by the Indians for purifying the land. The site of bloody rituals to help its further growth and purification. The moving leaves, carried by the leaf-cutting ant, the only insect that can carry 2-3 times its weight.

During a short boat ride down the River Bartola, the water that separates the reserve from non-reserve land, we watched turtles sunning themselves on logs, herons standing delicately at the water’s edge, chocolate spider monkeys crossing the river via tree boughs, and balete fish, with piranha-like teeth, used for eating fruit seeds that fall into the river, jumping up from the water.

After a lunch of large river shrimps in garlic, we took the public boat back upstream to Sabalos Lodge. It is a series of cabanas on the riverbank, two kilometers away from Sabalos.

We are staying in the Tarzan cabana, a t-frame thatch hut located on the riverbank. We arrived to the sound of howler monkeys and entered a world of hummingbirds, salamanders, caimans and another assortment of forest life. On the upper level of our hut, we have a bedroom, bathroom and a balcony with a bench that look out right over the water. Downstairs, we have a pair of hammocks, where we can rock from side to side while taking in a bird’s eye view of the river and the green forested shore beyond.

The friendly local owner, a former Sandinistan general, treated us to juice made with small oranges upon our arrival, and later to sangria made from grapefruit, orange, lemon and jackfruit grown on his own farm.

Again, sleep with come early tonight. With no multimedia and light attracting bugs, it makes more sense to go to bed early and rise at dawn for a new set of activities.

I’ll walk back to our hut along a path lit by lemon-scented torches, listening to the music of cicadas and the croaking of frogs.

**the photos are of the blue jean dart frog, a caiman, and our riverside Tarzan cabana (which, by the way, is where Mark proposed)

El Castillo

October 3, 2006

El Castillo, a remote outpost, population 1800, on the San Juan River, is my favorite place in Nicaragua so far, and one of my favorite places ever. WE have only one night here. But I’d love to return, spend days reading and writing on the balconies overlooking the river, listening to the hum of insects and rumble of rapids, and eat fresh fish and coconut bread daily.

It required a long journey to arrive here. We lined up for boat tickets at Granada’s dock yesterday at 11, then returned to board at 2. Despite a 3 p.m. departure, we were among the last to arrive and first class was nearly full, relegating us to seats on the end of a table for six.

First class passage to San Carlos, which cost $7, meant a spot in the overcrowded upper deck. Five sets of benches, divided by a table, plus two straight benches were in a small, air-conditioned room.

The experienced passengers not only saved themselves room on a bench, but they brought a hammock or comfy chair to string up on deck, or a mattress to claim corner sleeping space.

We pushed off from Granada and I watched it recede, a view of yellow and pink colonial arches and building, a shore lined with palms and coconut trees. In all directions, a thick green forest spread away from Granada, rising up to the cloud-covered volcanoes, shadowed by rain in the distance.

People passed the time reading, playing games, watching TV, trying various ingenious positions to sleep or eating. I ventured down to second class, where a woman served cold sodas, chips and chicken with rice and fried plaintains through a window. She could look out at the second class passengers packed into hard wooden benches, the floor below wet and grimy.

We made a stop at Ometepe, an island with two volcanoes in the middle of Lake Nicaragua (Cocibolca). There, men carried aboard large baskets of plantains and watermelon for shipment.

At a 3:30 a.m. stop at San Miguelito, on the opposite coast, children came through the boat selling coffee with milk, tortilla with cheese, bread, as though being on the docks, selling in the middle of the night, was a natural activity for them.

The floor in first class was more or less clean. So as it got later, more people dipped onto it. I went down to the cold and hard floor first. Mark later switched places with me. I wished I could have taken a photo of first class, Nicaraguan style, with bodies curled under tables, laid out in aisleways or spread across benches. Those who’d strung their hammocks on the side of the boat had to cover themselves with sheets of plastic as protection from the rain.

I woke up to smooth waters, a calm sky, a pastel world holding the green pearls of the Solentiname islands. We disembarked in San Carlos, a muddy, colorful, decrepit town, surprisingly active at 6:30 in the morning. We found a place to sit at the plastic chairs and tables of a small comedor. There, we could watch the locals eat large, fried breakfasts of gallo pinto – fried eggs, beans and rice, meat or fried cheese, together with sweet iced fruit drinks or cups of coffee – and the bus attendant receiving one after another large bundle of squawking chickens from the top of the bus and dropping them gently in the mud for passengers to claim.

We boarded a 50-passenger covered longboat for the 2.5 hour trip down the San Juan river to El Castillo, the end of this route. The San Juan river runs along the border between Nicaragua and Costa Rica and connects the Atlantic Coast with Lake Nicaragua. It used to be an active route for transporting gold and other goods, as well as a popular roaming ground for pirates. At one time, it was considered as the most logical place to create a canal cutting across Central America.

We’d only passed one sizeable settlement on the way, the riverside town of Sabalos. El Castillo lay at a bend in the river about 20 minutes further, just before a series of rapids. Until recently, when San Carlos-San Juan del Norte boat service resumed, El Castillo was the end of the line.

We stayed in the Hotel Albergue El Castillo, a two-story wooden hotel overlooking the water. Owned by the mayor’s office, it had wonderful hammocks and rocking chairs on the balcony, where one can fall asleep to the rush of rapids.

There we learned that the majority of visitors are European. Despite the much closer proximity compared to Europeans, only 8-10% of the hotel guests are Americans.

“I suppose the Americans aren’t as interested in eco-tourism,” the hotel attendant theorized.

After a wonderful lunch of rubalo (a fish that swims upriver from the ocean into Lake Nicaragua) we went to visit the crumbling stone fortress, El Castillo’s hilltop sentinel.

El Castillo de la Inmaculada Concepción de María was built by the Spanish in 1675 to protect Spanish settlements (including Granada, on the lakeshore) from pirate attacks. At the time, it was the largest fortress in Central America, with 32 cannons and 11,000 weapons.

In 1762 it was the site of a major battle between the Spanish and British in the Seven Year War. A 19-year-old woman, Rafaela Herrera, seized command of her father’s troops after he died and succeed in driving the British off.

In 1780, Horatio Nelson successfully captured the fort by arriving on foot. But after nine months there without reinforcements, he and his sick soldiers went home. We then strolled through the streets of El Castillo.

Accessible only by boat, El Castillo had one central street, or rather a walkway, of alternating stone and concrete. Wooden homes, shops and hostels on stilts lined it, painted green, blue, red, yellow, pink and grey. The children played on swings and slides along the riverbank and wore blue and white uniforms to the hillside school, set among palms and tropical foliage.

The place gave me such a feeling of calm and relaxation. It felt removed, safe, beautiful and unique. I dreamed of returning again some day, to spend a whole week reading and writing from a hammock, eating fresh fish daily.

By six, darkness fell. And by 8:30, the entire town had gone to bed. I joined them, closing my eyes to the sound of the nighttime insects, letting my thoughts flow with the water outside.

Granada

Mark and I began our adventure in Nicaragua today with a volcano andCanopy tour. I appreciated both getting out of Nicaragua and lettingourselves be led about by professionals. It was the kind of slower pace and care I needed after my nasty incident on Friday night. My black eye is shining nicely today, but there are plenty more compelling things tolook at in this area.

A canopy tour is a series of ziplines and platforms set up in thetropical forest. The first one, which is the one we visited, was setup by a Canadian. The idea came from the man featured in the movie,The Medicine Man. Tired of going up and down trees, looking for theplants that could cure illnesses, he set up some ziplines that wouldallow him to glide among them. And now tourists can enjoy the fun.

We lumbered up an extremely rough and rocky road, past coffeeplantations and farms that raised peliguey – a funny lookingcombination of a sheep and a goat, made in Cuba, and supposedlydelicious barbequed.

The staff at Mombotours was very professional and safety cautious.We had four guides for only four tourists and they basically dideverything for us – outfitted us in harnesses and chains, gave us ashort explanation, and then hooked us and unhooked us at each stage ofthe journey.

All we had to do was let go of fear and slide along the cables, ourfeet brushing through the tropical leaves, our yells sounding like thehowler monkeys we saw upon arrival. It was great fun to slide overdense greenery, to move through it as the animals might, and to viewit from a different angle. Many of the trees we landed on were giant, majestic species - guyavon, ceiba and royal cedar.

We travelled a total of 600 meters on the course, then had a nicerappel at the end. Walking back to the lodge, which looked out overLake Nicaragua (also called Cocibalca), we passed coffee bushes,avocado and grapefruit trees, banana and cocoa plants. We picked red coffee beans and sucked on the sweet seeds. Our guide, Jay, took acocoa pod. At the lodge, he opened it and instructed us to suck onthe sweet white covering on the cocoa beans, which tasted like alittle red spiky fruit I´ve had here.

From there, we drove to the Mombacho volcano, my first volcano visitin Nicaragua. We entered the park and drove up the steep road to theedge of a crater. In the 1980s, this area had been a military base.But funding from the U.S., Britain and France helped turn it into atourist area, which according to Jay, has been very successful.

At 1150 meters, the air was fresh and clean, a light breeze blowing,the cloud forest greenery covered by dew. Jay led us along a patharound the crater, pointing out various plant life. We saw manybromedias, the candlestick-like plants that can hold up to three orfour liters of water. Salamanders sit inside of them waiting to catchtheir prey. Its because of these plants that the forest stays wetcontinually. We saw sleeping plants, that fold up upon touch, the colaliyo, whose leaves are used for hats, and the orange bird ofparadise, on which hummingbirds feed.

We visited the smoke holes, where hot steam continued to rise, eventhough the last eruption was in 1575. And we enjoyed a wonderful viewof Granada, Lake Nicaragua, the isletas (a series of small islands inthe lake) and the nearby volcanic lake, warmed by the underground steam.

In town, I tried the Granada specialty, yucca, fried pig skins andvinegared cabbage served on the leaf of a plant we saw on the Mombachovolcano.

Yellow, pink, ivory and blue colonial buildings fill the town, wherehorse-drawn carriages roll by, as well as a tacky train, filled with local tourists. On the central square, I watched a vendor scoop ahomemade chocolate drink into a plastic bag, put in a straw, tie itinto a knot, and hand it to two little girls, who bent their heads together to eagerly suck.

A Warning Regarding Taxis in Managua

This is not meant to scare visitors away from Nicaragua. Outside of the capital, Nicaragua is filled with splendid greenery, culture, natural and historic places.

But Managua is not a pleasant place and I advise skipping it if possible. If you absolutely must spend time in Managua, then be very careful when choosing your transportation.

I’m writing about taxis because I was assaulted and robbed in a taxi yesterday. But knife-point robberies are said to occur on buses.

The typical Nicaraguan taxi picks up more than one passenger at a time. Whoever gets in second or third may have to go out of their way before reaching their destination, but the price is correspondingly reduced.

Yesterday I got into a taxi that already had a passenger in the front. The man was counting his money and, I assumed, preparing to pay and get out soon. I sat alone in back, behind the driver, where I (mistakenly) felt more safe. After we started off, the driver locked the door behind the passenger, which I thought was strange, but figured he must be doing it for safety. Robbers have been known to enter cars, especially when stopped at stoplights. My door, however, remained unlocked.

Not long afterwards, and with incredible speed, the passenger jumped back on top of me and began punching me in the head. He pulled my shirt over my face to keep me from seeing and I found myself in total blackness, trapped in a car with two strange men, and being beaten. The second I saw him flying towards me with a grunt, I began to scream, a loud, insistent, instinctual scream of terror. Not knowing what they would do to me, nor if I would even survive, I was truly terrified.

He yelled at me to shut up and beat me harder. I remembered my unlocked door and tried to find and reach the handle in the blackness, but he’d trapped my left arm and I couldn’t move.

He began to ask what I had – how many dollars, cordobas, did I have a cellular phone. I had all that – plus more – a camera, an ipod, an electronic dictionary, souvenirs, a backpack. And I was unusually loaded, as I’d planned to treat my colleagues to dinner that night and needed to change money for my upcoming travels.

At this point, it seemed their main motive was robbery which was a comparative relief. I’d give them everything to not touch me or to take my life. I told them, from under my shirt and under the weight of his body what I had – begged them to take it all, to let me out.

It became clear the robber and driver were a team. They told me they were taking me outside the city, said I needed to keep quiet and cooperate if I didn’t want to be killed.

The robber, who said he was from El Salvador, and asked where I worked, gave the driver directions. He also said, to my relief, that my body didn’t interest him. The driver gave the robber instructions – Take her shoes.

He pulled off my shoes and my watch, felt for rings or necklaces, felt for money hidden elsewhere on my body. I understood they would probably clean me dry, then dump me somewhere. I imagined a remote rural area, a dangerous barrio. I imaged they’d roll me out while moving at full speed and again the terror intensified. I asked them to please stop before pushing me out.

They did slow to a near stop and did push me out onto the road. I was barefoot, my shirt over my head, shaking and disoriented. I had nothing but 10 pesos (about 50 cents) I happened to be holding in my right hand.

When I staggered up to a security guard watering the lawn, he told me where I was. Luckily, it was a decent area. And luckily, I came across the guard first, because the next figure I saw was a guy walking down the street with a baton.

I told the guard what happened and he helped me to get another taxi. He told me when he’d first seen me walking towards him, he’d thought I was crazy.

I had no money, no key to my home, no cell phone, and no ones numbers memorized. If I hadn’t been on my way to meet colleagues for dinner, I don’t know what I would have done. Since they were waiting for me, I was able to take a taxi to them, ask them to pay for the taxi, and ask for their help in canceling my credit card, getting shelter, etc.

In summary, it was a frightening and miserable experience. When in Managua, it’s preferable to have a car and driver. If that’ s not possible, ask anyone you know there for names and numbers of known, trustworthy drivers. Or, use only radio-controlled taxis offered by a reputable hotel – which will cost more, but are reliable. Barring any of that, never get in a cab in Managua with other passengers, and tell the driver you want express service (which will cost a little more). This means he can’t pick up other passengers while you are in the car.

Ideally, especially if you are alone, it’s good for someone to walk you to the taxi and to note the car number. In case of last resort, choose cars only with the newest taxi plates (3 horizontal stripes) and note the taxi number before getting in.

The risk is real and for your health and safety, Managua is a city in which one must take precautions.

Another period without photos

Due to a robbery in a taxi on this day, I lost the blog entries I was preparing, as well as my camera. So I no longer have anything to post about my very interesting visit to the rural, mountainous, Rio Blanco, my motorcycle-ride, horseback-ride and hike up to visit a remote cattle farmer, or the fun evening birthday celebration a local employee invited me to for his daughter.

I’ll also be without photos, until I’m able to replace the camera. Two cameras lost in two months. I’m not batting very well.

Typical Nicaragua

September 17, 2006

I returned to Nicaragua after a weekend away and immediately felt right back at home. The taxi driver I had asked to pick me up at the airport didn’t seem to be there. I found another (who was very responsible and nice). But, typically, he had to stop at the gas station on the way. Managua drivers, rather than putting their fares into gas, drive on empty and seem to put in only enough to get themselves to the destination of their current order. I’m not sure why this is (lack of funds, fear of gas theft?) but I should ask.

At the gas station, I went into the mini-mart to buy some milk. On my way out, a large white truck suddenly revved up and roared backwards. An empty beer bottle fell out of the cab and crashed against the concrete. I just missed being hit. My taxi driver, Jose, looked on open mouths. He refused to move until the truck left.

“Look,” he said, as the female driver got out, giggling and swaying and moved back into the cab. Her male companion took the wheel, holding a half empty bottle of Corona in one hand, staggering as he gripped the wheel and climbed into the cab. “They are drunk. It’s very dangerous.”

We watched the driver take another drink, hanging on to his open bottle. He looked through the window with rolling eyes.

“Isn’t anyone going to stop him?” I asked.

No. Jose said that if the police saw him, they’d stop him. “But there are few police in the city. So they usually come on duty at midnight. At 9 p.m., there were neither police, nor pedestrians, on the streets.

The white truck pulled out into the fast lane into town, accompanied by a minivan that Jose said was also driven by a drunk driver. If they want to risk their own lives, I say go ahead. But what I found unfortunate is that cars, pedestrians and bicycles would all be hostage to those giant vehicles, liable to spin out of control at any time left. If any one died, it would most likely be an innocent.

Also, typically for Managua, a light evening rain fell, and the lights were out, leading us to drive down black streets.

I asked Jose if the lack of electricity was seasonal.

“It’s only been a problem this year,” he said. “Before, we had enough.”

I felt fortune smiled upon me when I found electricity working in my apartment, leading me to not mind the lack of water so much.

Promising Exports

September 14, 2006

In 2005, Nicaraguan exports were $857.9 million, a 45-year high. Nicaragua had $600 million in the late 1970s. Exports then plummeted, as the country went through turmoil and war, not reaching the same level again until 2000.

The leading export products are: peanuts, black beans, milk, gold, beef, shrimp, lobster, fish and hammocks (good stuff!:))

Other products gaining increased export share include: honey, melons, okra and watermelon.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Upcoming Holidays

September 13, 2006

Relating to the entry below, Awilliam today told me about the Sandinistas efforts to reduce illiteracy and poverty in the rural areas – by requiring high school and college students to spend five months in the most remote areas, teaching reading and another three months picking coffee or cotton.

Awilliam lived in a remote mountain village. He spent a short time picking cotton in the west of the country, but when the heat overcame him, he asked to transfer back to the mountains to cut coffee.

He didn’t seem to have very positive recollections of his service.

He recalled working together with several hundred other students in a coffee hacienda that had been confiscated from a well-to-do landowner.

“Every morning we were woken up at 4 a.m. to wash in the river. It was so cold! And the food was always the same – beans and tortillas for breakfast, beans, tortillas and egg for lunch. There were a lot of people who had stomach problems from so many beans. In the morning, we had to gather and sing the national anthem and the Sandinistan anthem.”

He began to sing it with a smile of derision. “We’ll fight against the Yankees and the enemies of humanity…”

“We wore military clothes and carried guns for protection. Sometimes we came across snakes or red-eyed frogs and the women’s screams echoes across the mountains.”

Looking at Awilliam’s gentle, intellectual face, the father of two daughters, it’s very hard to imagine him as a military and propagandistic tool of a political regime. But the faraway news that formed the distant reality of my junior high civics class was his life.

I asked why rural teachers couldn’t teach the illiterate in their communities to read.

“They could have,” he said. “But in addition to teaching people to read, the government wanted to make a show. They wanted to say, see, we are sending you people and making you a priority.”

The next two days are national holidays. Tomorrow is the anniversary of the 1856 battle of San Jacinto, the final battle of the 1856-57 National War. This was the battle in which many Nicaraguans, aided by Guatemalans and Costa Ricans, drove out William Walker, a nutty American who, as only one small event in the long history of US intervention in Nicaragua, had himself installed President, made English the national language and legalized slavery. This battle finally drove him out.

The 15th is Independence Day, when Nicaragua, and other Central American countries, received their Independence from Spain in 1821.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

The Causes of National Poverty in Nicaragua

September 13, 2006

Today, La Prensa newspaper carried an editorial that listed the 11 main causes of national poverty in Nicaragua. I thought I’d share them with you, summarized and translated into English. The piece was written by Edmundo Davila Castellon, a civil engineer and graduate of Incae (I believe that is a respectable university here).

1. Complete disregard for the national demographic explosion at 2.7% annually. Nicaragua has had the highest population growth in Latin America.

2. Megasalaries, pensions and benefits, which affect the transport, education, health and work opportunities (cost and availability) for others.

3. The national budget, which doesn’t take care of the population’s social needs.

4. Peasants migrating from the countryside to the city.

5. Degradation of animals, plants and nature.

6. Internal and external debt.

7. Ungoverability and political, social and economic factors that directly affect the economy, social peace and national and foreign investment.

8. Illiteracy and the lack of basic education

9. Frozen pensions, which don’t take into account devaluation or inflation.

10. Problems with property rights

11. Government corruption and wars

Any thoughts on the validity of this analysis? Are there causes that have been omitted?