August 9, 2006

Before leaving Talas, I managed to see the two most popular tourist sites. Manas-Ordo, or the Manas legend complex, is such a part of the local characters that people say if you haven’t been to the Manas complex, you haven’t been to Talas.

Manas is a Kyrgyz legend about a hero, Manas, who searches for a home for his people. Together with his advisors and knights, he battles larger foes, until winning a battle at which he is killed.

Probably based on the experiences of a range of military leaders, their achievements are ascribed to the character Manas.

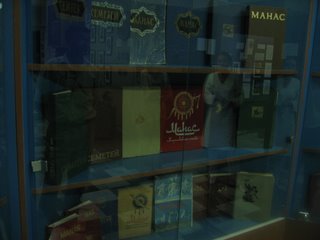

While books of the Manas legend are available, even in English, the Manas legend is traditionally passed along orally, by storytellers called manaschi.

The complex, including a horse track, a museum, a rose garden surrounded by 40 statues of his soldiers, a sheep-slaughtering site, and a yurt where fortunes can be told, was built in 1995, during the 1000 Years of Manas celebration. The complex makes Manas out to be a real character, saying he weighed 10 kilos at birth, was 2.5 meters tall in adulthood, and lifted a certain large rock (placed outside his grave) before each battle as a sign of luck. If he could lift it, everything would be OK. If he couldn’t, it was a bad sign and he wouldn’t go.

At the museum, they say that Manas was born in Talas, he grew up in Talas, they found the grave of a matching man (2.5 meters tall, 60-70 years old) there. What certainly does give the otherwise undistinguished Talas valley fame is that it was the site of a decisive battle between Arab (Turks, Arabs and Tibetans) and Chinese in 751. The Arabs success in driving out the Tang Chinese army brought Islam into the region and changed the course of Central Asian history.

Besh Tash (Five Rocks) is a national park, located just 17 kilometers from the town. It’s a beautiful place. A rapid crystal-clear river moves through the valley, treeless, rocky peaks arising on either side. Yurts dot the pastures, while men on horseback gallop down the rocky dirt road.

Given the lack of rain, it was already dry and brown. But as we ascended, we found some green hills. If I’d wanted to spend my weekend in the most beautiful spot, I probably should have come here. But I instead wanted something a little more unusual, wanted to experience some cultural tourism. At least I got to see what the park looked like.

On my final evening in Talas, I moved from my village yurt to a Community Based Tourism guesthouse in town. My host family was quite well-off. Their 22-year-old daughter Elmira had already been to the U.S. three times. She just finished her studies at the American University of Central Asia, which cost her parents a pricey $1700 per year tuition. She was at home, after quitting her job at the Soros Foundation because she considered the $200/month salary too little. She’s planning to work for a phone company on a U.S. military base in Afghanistan for $500 a month.

The family had a yurt in their yard, a car, a computer, internet access, a satellite dish, a washing machine, a refrigerator.

While Bermet sat next to me in the candle-lit yurt, stirring the pot of koumiss (fermented mare’s milk) as I ate my dinner, I asked her if she wasn’t scared Elmira could be stolen during her summer break in Talas.

“No,” she said. “My daughter has a different mindset. She’s been in America and she doesn’t think that way. People here know that and they know she wouldn’t stay if she was stolen.”

“Would you help her to leave?”

“Yes,” she said.

I was interested how Bermet acquired such a modern attitude, how her husband supported her, what led them to challenge the traditions that seemed so perverse in the Talas region.

“My husband stole me,” she whispered, which made the question all the more intriguing. “I was a village girl then and I didn’t know any better.”

I asked how she felt about it. She hesitated.

“I don’t have any regrets now,” she said. But at the time, she hadn’t wanted to marry him. They hadn’t dated before their marriage.

Shortly after she told me about how she supports her daughter’s free decision, she told me that she is urging her daughter to find someone to marry.

“What’s the hurry I asked?” spooning into my spiced rice with carrot, fat and chunks of beef.

“You know,” she whispered. “They still check a girl on her wedding night.” Despite all her modernity, despite Elmira’s education and travels, her private sheet

would be inspected after her first night with her new husband. And Bermet feared that if she waited too long to marry, she’d be tempted into immoral activity, she’d become an impure wife.

I told her what Medina had told me. That if the husband knew his wife wasn’t a virgin and was OK with that, the family would hide the information.

“Yes,” she said. “If the relation was only with him before marriage. But if it was with someone else, he’ll always think of her differently. I don’t think he’ll ever be able to truly love her.”

When I left the next morning, I asked to photograph the couple. Bermet wrapped her arms about her husband’s chest in an unusual sign of open affection. He, embarrassed, pushed her back. She took offense by moving away from him and crossing her arms across her chest. In the photo, he pulled her back to him. His arm is around her shoulder. Her arms remain crossed, but she wears a smile. They seem happy.

1 comment:

Dear JJ, could you perhaps get in touch with me? I'm Ben, founder of neweurasia.net, an online magazine about Central Asia. I have a question about one of your posts published on your blog.

Many thanks! Ben

Post a Comment